Chapter Text

The most cliché way to start a story is with a birth. Be it a stormy night or a sun-drenched day, what could go wrong with a kicking baby and its piercing wail? A lot, it turns out. Varric’s own birth was uneventful. His father wasn’t even home. Bartrand had fetched the neighbouring women, and then hid under the table as their mother screamed.

All together it had been a boring affair. A runt of a boy, he had slipped from her like the yolk of a cracked egg. His mother has told him that no one cleaned him first; he’d been given to her still wet with purple, red and blue, and she had to towel him off until the full head of his fair hair had stood straight up in tufty tresses. He had been blonde back then, with colours his mother didn’t have words to properly describe until she’d been forced to the surface and saw the sunlit wheat fields of the Free Marches for herself.

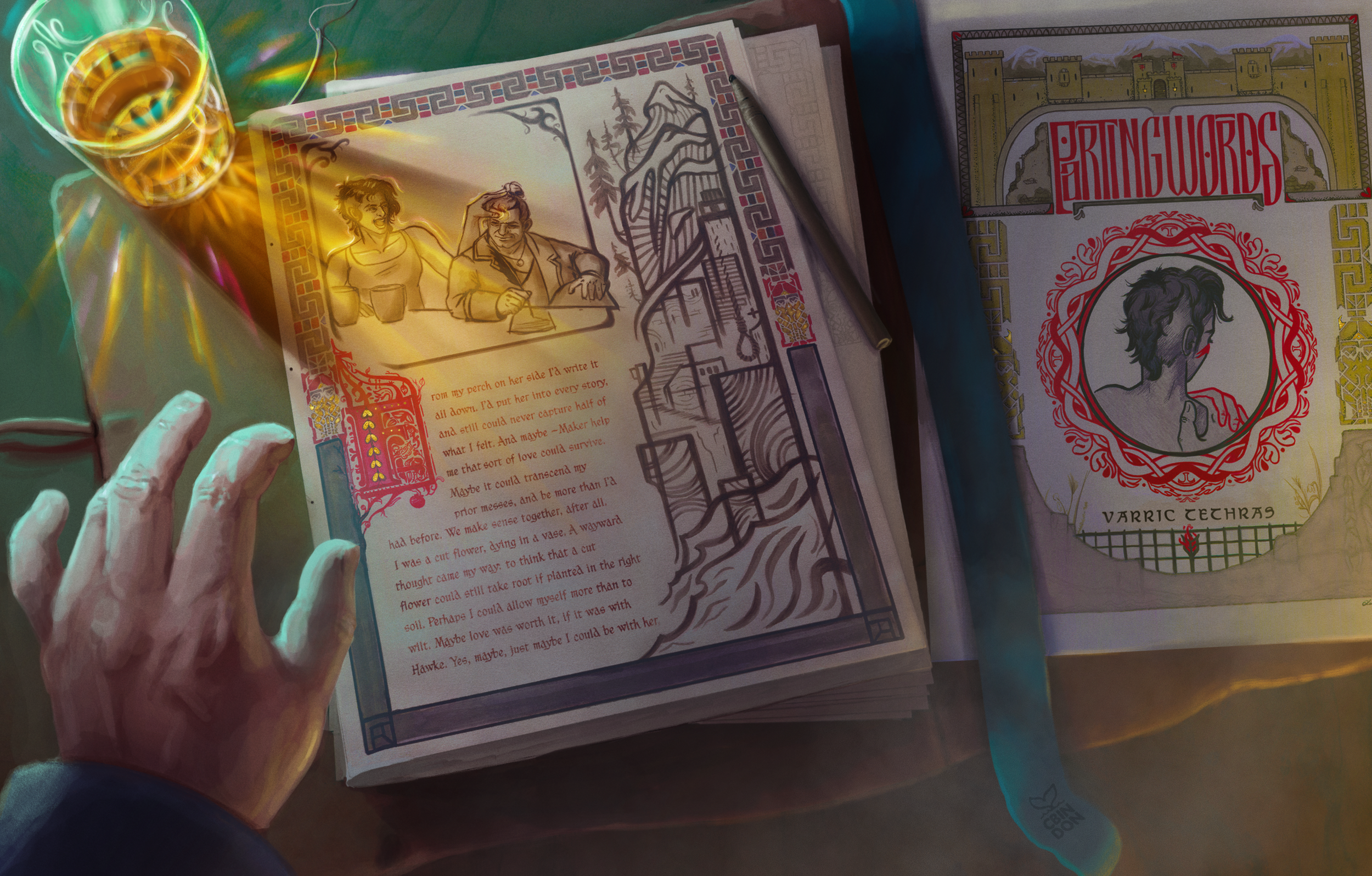

An easy birth is a good thing, but while great for mother and child, it makes for a terrible story, and an even worse start to one. It’s made all the poorer for the fact that this story isn’t even supposed to be about him. Crumpling the piece of paper, Varric sighs and pours himself another glass. The red wine is a Silent Plains Piquette, and the spoils of a Herald’s Rest heist that Cole had unwittingly aided him with. It’s already half-empty, and he’s going to need all of it to get anything worthwhile to stick to the page.

Despite what others may think, he’s not good at writing about people other than himself. There is always something of him there, even after his first two books, when he learned not to make all his protagonists young dwarven men in order to obscure the extent of Varric within them. This story, however, is supposed to be about Hawke, and he wants to rush through all the prerequisite ways in which to begin. He knows none of them are good enough, and he wants to exhaust them as quickly as he can, so that the real story can start. And so, he begins by her birth, too.

Marian Hawke was born in winter—a child made in more hopeful months, when the weather was warm and everything felt easier. But such was the way of the world; loans taken in spring must be paid when warmth was far away and cold encroached on your walls.

“She cried that entire winter,” Leandra had told him. “Malcolm had no idea what to do. Truth be told, neither did I. I’d swaddle her as good as I could—rock her the entire night. She was always loud, my little girl. Right from the start, she was loud.”

Varric stretches—arms above his head makes his joints crack—and gifts himself another mouthful of wine. It goes down easy—too easy—and he tries to remember if this was ever hard for him; if a younger version of Varric choked on Dragon’s Piss, got a coughing throat from a dry, sour white, or had his head spin from the deceptively sweet blend of dark rum and orange liqueur. He doesn’t know what finally did it—what it was that made him sit down to write something for just him—but perhaps it’s as easy as that: a sip that loosens his mind and makes movements stir in his writing hand. Or perhaps it’s a lot more complicated than that.

With The Tale of the Champion he had wanted a chronicle of what he had already known would be a war, the escalation of which had been skewed in the collected minds of Kirkwall before the air had time to clear from the dust and debris of the ruined chantry. She had been there, of course—she was the Champion—but it wasn’t the version of her that was most dear to him. The things that had been pulled from him in the harshness of an interrogation room is not what he wishes to write now.

Even as the interrogation ended, the questions did not. His time away could be measured in the strings of echoing inquiries. Through an cascade of “Did Hawke really take out six guys by herself?” and “Is she actually as tall as the book says?” her very name has become something foreign to him.

Hawke is the name of a hero now. She is a staff with a blade attached. She is a stiff-necked mabari who defeats her adversaries in single combat, and has time for a quip when she’s done. The Hawke he put on the page is larger than life, while the real thing is just life to him. He wants to find his way back to her—his Hawke, rather than the legend he made her out to be. He wants to wake and find himself among wind-worn spires and salty air—in his pigsty of a city, with its statues in chains and with a Hawke the details of which would have never been mentioned in The Champion. He guards them too dearly, holds them too closely. Spins them in his mind until they are whittled and worn.

The Hawke he knows is gritty and unrefined. Taut muscles and a tang of sweat. She always has dirt under her fingernails, no matter how short she keeps them. She chews with her mouth open, and laughs with an even larger maw. Despite the rough edges, there is also something delicate about her. She checked in on Merrill every day for her first months in the city, through countless trips to the market together, and spare coins presented with enough tact to not be thought of as charity. She hides it poorly, this well-known secret of her heart: despite the hardships of her life, his Hawke is kind.

Perhaps it's the simple passage of time that drives his pen. A year had passed since he last saw her, and her absence feels like a thorn in his side. It's banal—an embarrassing aside in the midst of an apocalypse, but he misses her. Misses her more than he has ever missed another person. The sky is torn in two and spitting demons, and yet his two biggest issues of the evening are the Hawke-shaped absence across his table, and finding the words to write about it. The Hawke on his page won’t be as vibrant as the one he’s come to know—no blood will darken her cheeks, no smoky scent will find its hiding place in her dark hair, and no joints will crack as she flexes her fingers over the table—but if he does it correctly he’ll look at it and see her there, in the words he has written.

“You’ve really captured them” writers are sometimes told, if they are good enough for the praise to apply. As if the essence of their subjects have been plucked, wriggling and whining from the teeth of a trap and injected into the work itself. This is what Varric hopes for. Like a butterfly, he wants to pin and preserve her to the paper so that he may trace the outline of her silhouette with ink. He wants to arrest her in the cage of an on-the-nose description; to capture something of her on the page. Not for the eyes of anyone else, but just for him. A piece of her that he can keep.

To what purpose? That he doesn’t know yet. And there, perhaps, lies his true reason. The thing that most makes him dip his pen and pull it out, ink-dripping and dark with words—he doesn’t know fully how to think or feel about her yet, and when Varric doesn’t know what to think or feel, he writes. Here he can make his mind into something he himself can read. If Hawke is an all-consuming question mark in his head, then what better way to find the answers by putting them on the page? Why not conjure his Hawke in a way that exposes not only her, but also himself?

This has always been his way. As far back as he remembers, Varric’s mouth has led the way for his brain. It is through words that he makes sense of his world, and it’s through writing that he most easily expresses the sentiments still unclear in the fog of his mind. With a pen in his hand everything makes more sense.

It has been the case since his very first book, where his flimsily hidden thoughts about Bartrand and him had glared obvious from behind a story of two dwarven brothers on a Merchant Guild adventure. It had made Bartrand embarrassed, he remembers fondly. A reddish hue had crept from beneath the apricot braids of his still youthful attempt at a beard, and he had shaken his head while he praised him; still an old brother reading his little sibling’s first book, even as embarrassment overtook him and he had to cough awkwardly on the appraising words.

Now many books later, Varric thinks he has written enough about Bartrand. A Dasher’s Men was about him, Darktown’s Deal was for him, and Hard in Hightown: Harder and Higher was, three years after his death, something Varric thinks he would’ve finally enjoyed reading.

This book, however, is about Hawke, and even though he has written about her before she is far from an exhausted subject. Her form looms large in his mind, shape yet undecided like an ink spill, dripping and expanding in ever-changing frames. He needs the story to make sense of her, to confine her into a shape he himself can live with. And so it's born; a book to be written, but not to be read.

The fact that no one will read it should elevate some of the regular pressure of organized formalia and well-picked words, but in Varric’s mind, it makes it even more important. He may feed slop to the common folk of Kirkwall, but in this? This is the true distillation of his thoughts; a labour of love so unyielding it carpets his being like a blanket of grass, with myriad roots all able to live on almost no nourishment at all. No, this book can’t be on par with Swords & Shields, it needs to be good enough to breathe life into his tired arms, and plant some sense into his grass carpet brain.

And so, birth doesn’t do as a start to the story. Your birth says nothing about you. Many great men are born in brothels or barns, and many his lesser start their lives in castles. Andraste herself was born in a hut, and she rose further than any mortal ever has. No, the more he thinks about it, a birth really doesn’t matter at all. More important perhaps, is the other side of the eternal coin; a story may also start with death.

Varric rolls his shoulders; a pop among the ligaments, a hiss through the closed rows of clenched teeth.

He needs another glass of wine.

A sip of charcoal, and red fruits, followed by a dip in the ink.

Yes, a story may also start like this:

When Varric was two, his father died. Andvar Tethras did not live long enough to see the winter of his days. Driven to the surface, he had withered away like a deep sea fish washed up and flopping upon a beach. Varric has no memories of him, except for conjured things brought about by Bartrand’s words and a mother’s love. There is a flash of a face, the rhythm of a nursery rhyme, and vague shapes stained by copper and brass.

But what happens to a story, if you start it with death rather than birth? If he wants to, Varric can trace a narrative from the points of his parents’ deaths. He can pin the dates to a board, and connect it to himself with strings of red. Varric’s father died from giving up, and his mother died from drink. And so, when he was eight, Varric promised Bartrand that he’d never do either of them.

Still a boy, his brother had grabbed his shoulders and shaken him, his “Promise me,” said with just enough fear to give a young Varric pause. He had promised—he’d continue, in the face of terrible odds, and he’d never ease the journey with bottled comfort and buzzing thoughts. But Varric was a liar, and a cheat. He’s not to be trusted, and not just because he’s dishonest, but also because he’s weak.

To himself, he vowed to at least keep one of the promises—that’s all he can offer his beloved, stubborn, stupid brother. A tie between loyalty and lies, tenacity and lack.

An older Varric takes another taste of wine, and wipes his mouth. The death-laden paper crumples in his hands, and he puts forth a new page. The births and deaths of his tale doesn’t matter. They are writing exercises, at best. This is supposed to be about her.

A story may start with death.

When Marian was nineteen years old, her father died. Her father had been the spells she whispered behind the safety of their farmhouse walls, a controlled flame she held in her hands, and a coarse palm made soft when stroking the side of her face. More importantly, her father had been the one keeping the family together; the firm voice that settled the sour words between the siblings, the secret aside that made her mother smile.

When he died, they fell apart. Marian didn’t like to talk about it, but Leandra lacked her inhibitions.

“I don’t even remember the first two weeks without him,” she had admitted one night, when she, Varric and Bodahn were drinking at the Amell Estate. “I know we buried him. Marian told me as much. But I don’t remember it. Just Bethany helping me wash before we left, and that it was a sunny day.”

With her father dead, and her mother spent, Marian Hawke had found herself the new head of the family. Varric imagines her; a girl at odds with her world. A mage who’d not yet learned how to lie. His mind tries to conjure a form for her, when strength and muscles had not yet brought grace to her lanky frame. An unsure lip, her darting eyes, hands unequipped.

There was work for a youth like that. Marian had done it all. To keep the family afloat, she had mowed the fields of her neighbours until her hands, wet with sweat, slipped on the wood-grip scythe. She had hauled bricks on a cart for the Chantry, her strong back shaking to keep straight under the weights of labour and disguise. She had picked up weapons and picks, and ventured with daring men into the deep of the abandoned mines; come up covered in dirt, and with carts filled with ore.

For the rest of the family, her father’s death had been the loss of him. For her, it had been the loss of her childhood and the life she had led.

It's a pain Varric knows all too well. Every loss robs you of the person you were with them; an entire bit of yourself becomes a gift ungiven. He wakes in the morning as no one's son, bereft of the jokes he’d tell to friends long gone, and missing the child who used to play with his older brother. Likewise, the Marian that had risen from responsibility had been both less and more than her younger self.

When the ground burst with black and Blight licked at the soles of their feet, it was she who had made the decision to flee.

“You miss her,” Cole says.

The soft voice makes him jump—a splatter of ink a witness to the fright of too-close voices within enclosed walls.

“Kid, we talked about sneaking up on people!” Varric says, voice a bit higher than he would have liked.

“I didn’t sneak. I was here. You just weren’t looking.”

Varric pinches the bridge of his nose. “Maker’s breath…”

“The Inquisitor wants you tomorrow,” the spirit adds. “Hinterlands. Bandits. Lots of noise.”

“Great.” He corks his bottle—very little still remains. “Guess that means story time’s over then.”

Art made by Christina Bindon.